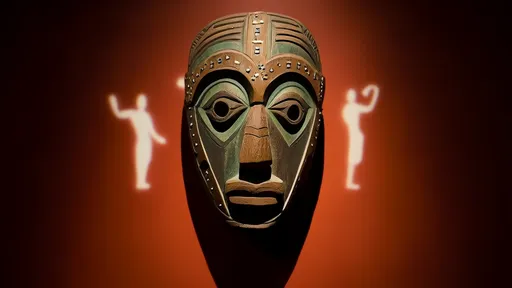

In the heart of Africa’s rich cultural tapestry lies the ancient tradition of mask-making—a practice deeply rooted in spirituality, community, and storytelling. For centuries, these masks have served as conduits between the physical and spiritual realms, worn during ceremonies to channel ancestors, deities, or natural forces. Today, however, the symbolism and craftsmanship of African masks are undergoing a profound evolution, as contemporary artists reinterpret these ritual objects through modern artistic lenses. This fusion of tradition and innovation is reshaping how the world perceives African art, bridging the gap between sacred heritage and global creativity.

The traditional African mask is far more than an aesthetic object; it is a vessel of meaning. Each curve, color, and material carries intentional symbolism, often tied to specific rites of passage, harvest celebrations, or communal healing. The Dan people of Liberia and Ivory Coast, for example, carve masks with serene expressions to represent wisdom and harmony, while the bold, geometric designs of the Baule people embody protective spirits. These masks are not merely worn—they are activated through dance, music, and ritual, becoming living embodiments of cultural memory.

In recent decades, a new generation of African artists has begun to deconstruct these age-old forms, infusing them with contemporary themes and materials. Painter and sculptor Romuald Hazoumè, from Benin, repurposes discarded plastic jerrycans into masks that critique consumerism and environmental degradation. His work echoes the aesthetic language of Yoruba masks while addressing urgent global issues. Similarly, South African artist Mary Sibande blends mask-like facial adornments with Victorian-era dresses in her sculptures, exploring identity, gender, and colonial legacies. These artists retain the spiritual weight of masks while expanding their narrative potential.

The global art market has taken notice. Once confined to ethnographic museums, African masks now grace the walls of avant-garde galleries and international biennales. Auction houses report soaring demand for both antique masks and contemporary reinterpretations, with collectors drawn to their layered histories. Yet this commercialization raises questions: Can the sacred essence of these objects survive outside their ritual contexts? Some argue that commodification dilutes their meaning, while others see it as a form of cultural preservation—a way to ensure these symbols endure in a rapidly changing world.

Technology, too, is reshaping mask-making. Digital artists like Nigeria’s Laolu Senbanjo use software to create intricate, mask-inspired patterns, which he then translates into body art or virtual reality installations. Meanwhile, 3D printing allows artisans to experiment with forms that would be impossible to carve by hand. These innovations are not without controversy; purists question whether a digitally rendered mask can hold the same spiritual charge as one consecrated through traditional methods. Nonetheless, such experiments underscore the adaptability of African artistic traditions.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this contemporary transformation is its democratizing effect. Social media platforms like Instagram have become virtual galleries where young African artists showcase mask-inspired works to global audiences. Workshops in Lagos, Nairobi, and Dakar teach mask-making alongside street art and graphic design, fostering cross-generational dialogue. The mask, once restricted to initiated community members, is now a shared cultural lexicon—accessible to all who engage with its power.

As African masks continue their journey from ritual objects to artistic statements, they challenge us to reconsider the boundaries between tradition and modernity. Whether carved from sacred wood or assembled from recycled metals, these faces speak a universal language of transformation. They remind us that art is never static; it breathes, evolves, and carries forward the whispers of ancestors into new creative realms.

, , ) are used. Let me know if you'd like any refinements!

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025